[ad_1]

Times are tough for craft beer. Once the darling of the tap walls and shelf sets, double-digit sales growth and taprooms springing up on every street corner like that green and white coffee giant. Things seemed like good times would never end, but every party has a pooper, and 2024 is looking like one of the most brutal years so far for craft brewery brands since 2020.

Yes, breweries are still opening, but many are closing their doors for good. Owners and operators are desperate to cut expenses and increase sales, diversify their revenue streams, or join forces with other small independent brands to form co-ops or beverage groups where costs can be dispersed amongst members. The sad part is that much of this writing was on the wall years ago – case in point, this 2022 article from Brewbound spotlighting a market survey of wholesale business by financial firm Jefferies stating that beer distributors were predicting a decline in craft beer sales over the next year. Did craft brands ignore the market warning signs or thought the worst would never happen to them? We will probably never know, but whether it’s the lack of business strategy, rising property taxes, escalating prices of raw materials, repayment of loans, wholesaler consolidation, increased competition, or declines in taproom foot traffic, craft breweries must make hard decisions about their business structures to push through the economic slump.

Cutting Distribution

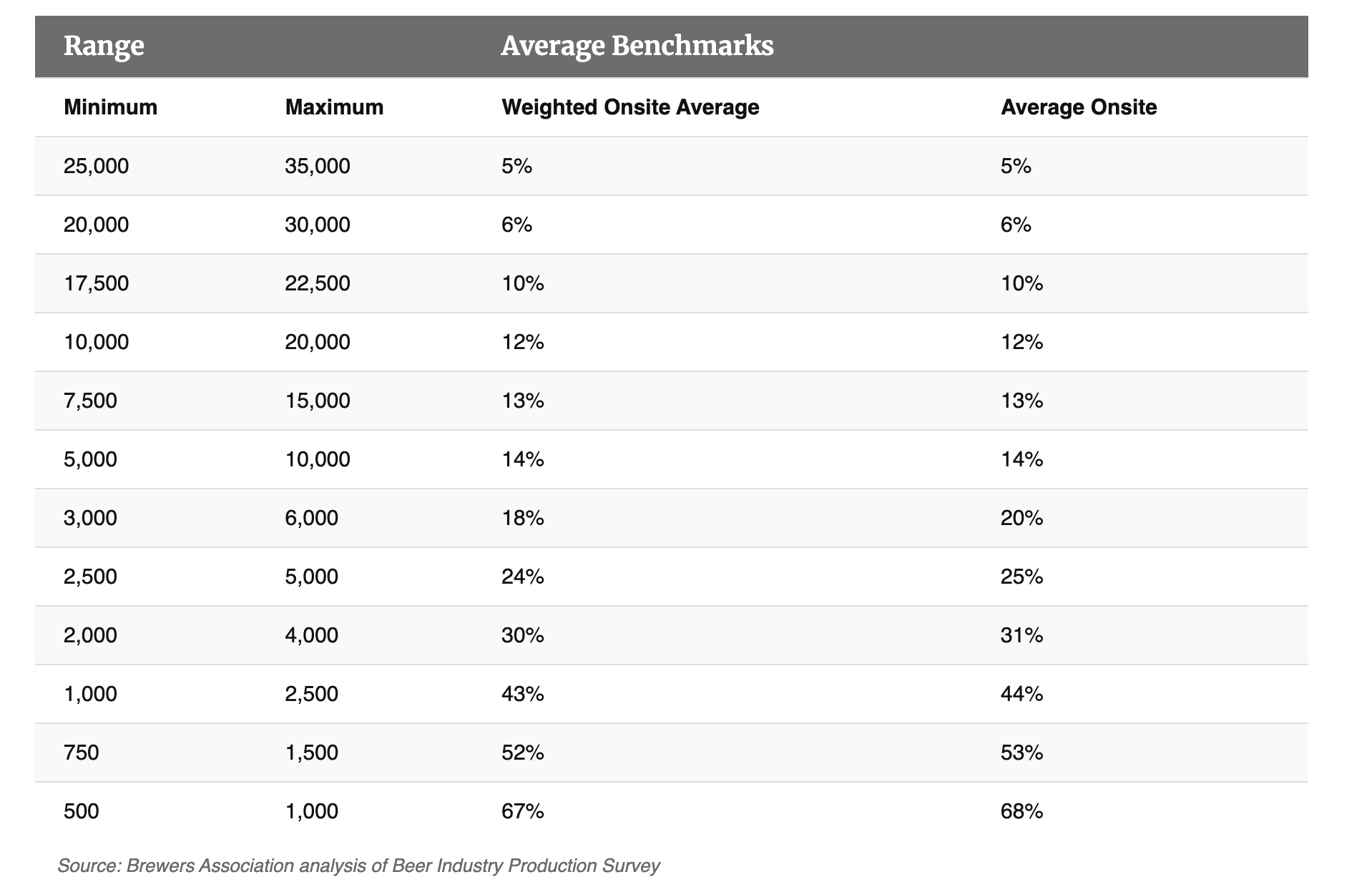

For many brands, selling beer in the wholesale channel doesn’t make good business sense anymore. Hocking cases and kegs at a low profit margin is not the ideal way to boost revenue – especially when off-premise sales velocity (the rate at which products are sold in retail outlets) has been lagging for the past few years. On-premise shutdowns in 2020 skyrocketed off-premise volume and rate of sales for craft brands. Breweries packaged everything they offered in the taproom, and now the result is an oversaturated and bloated selection of craft beer on shelf sets nationwide. In a BevNet article from April 2023, Zoe Licata heeded warnings of a culling of craft beer based on market data from Circana that showed a 4.7% decline in craft beer dollar sales from 2021 to 2022 and a forthcoming 4.2% decline for 2023 year to date (BevNet, April 2023). Inventory sits and collects dust in warehouses – dollars wasting away with every day closer to that batch’s code date. And those are the woes of the folks that are self-distributing. This problem is compounded when your brand is aligned with a wholesaler, which cuts even deeper into your precious profit margins. Toss in the regular expenses of doing business wholesale – sales rep salaries, travel expenses, point of sale material costs, promotions, etc. – and this revenue stream looks downright miserable. Not to add insult to injury, but SKU rationalization trends within distribution houses have become commonplace, combined with wholesaler consolidation across the US, and these elements don’t make the wholesale channel look any better. This issue seems to hit the smaller brands hardest – those under 5000 BBLs. According to a recent report from the Brewers Association, craft brands producing around 7000 BBLs and beyond annually seem to be still doing okay in the wholesale channel, with 70% or more of their sales coming from offsite sales (Brewers Association, June 2024). Craft brands such as Creature Comforts, Deschutes, Ninkasi, and 21st Amendment have withdrawn from expanded distribution to concentrate more on their home markets and go back to the adage that you build up a brand in your backyard first because it’s much more difficult to sell further away from your home base.

Slashing Budgets

Another recent trend involves assessing craft brewery overhead costs and making corresponding budget cuts. There are only two ways to improve the health of your business – cut expenses or increase revenue; when increasing revenue isn’t working, the former is a necessary evil. One way to cut costs is to try to renegotiate raw material contracts. While this works for some craft brands, not all have this option, so they must find other ways to cut dollars from their balance sheets. Not to be morbid, but many breweries successfully purchase production equipment at auction from shuttered breweries to scale production more efficiently and, in turn, cut costs. Forming or aligning with a brewers’ co-op or beverage group is another way to cut raw material or other expenses. The most high-profile example is CANarchy Craft Collective, although many others exist on a much smaller scale, and now that arrangement is dominated by the gargantuan Monster Beverage Corporation. You can share the load by rallying together and dispersing expenses amongst members. The final way to cut costs is probably the hardest for most small craft brewery owners – you have to reduce labor costs, which usually means cutting back hours or laying off staff altogether. This is the only choice for many brands right now, and owners find themselves in a situation reminiscent of their start-up days, working the brew deck or managing the front-of-house team. Finally, and unfortunately, another casualty of cutting budgets is retracting marketing efforts. This is probably the most counterintuitive measure because the less you get the word out about your beers, the fewer people will buy them.

Shutting Down On-Premise

Still, many craft beer brands are taking a different course of action that defies recent market trends – they are closing their own on-premise facilities and choosing to sell only in the wholesale channel. The allure of direct profit margins in your taproom has spurred tons of new openings over the past few years. Taprooms in the US topped out at almost 2 million in operation in 2022 (Brewers Association). But what looks easy on social media is pretty complicated when you pull back the curtain. These craft beer brands with multiple taproom locations have strategically plotted expansion plans and acknowledged real estate interest rates, projected sales figures, overhead costs, price points, entertainment options, hospitality training, and food programs- prime examples being Monday Night, Mobcraft, and Hi-Wire. The beer is still the common denominator, but the experience rules the roost, which is new territory for most taproom operators. So, some craft brands have made the difficult decision to forego the overhead costs of a brick-and-mortar location by shutting their doors to the taproom but retaining the brand rights to sell in the wholesale channel. Craft brands like Cape May, Gigantic, and Rogue have shut down satellite taproom locations to focus more on production and distribution, while others like TRVE and Ale Asylum have shut down their taprooms completely and moved production to their facilities. Production arrangements are varied, but most craft brands take on a co-packing partner or contract brewing relationship to get the job done.

Pivoting Product Lines

But not all roads lead to closures or cutbacks. Some craft breweries are expanding their product offerings to reflect consumer demands in the marketplace better. While the non-alc route is tempting, many breweries can’t shoulder the expensive production costs of removing the “alc” from their beers. Yet some have skirted this aspect by producing hop water – a zero alcohol, better for you hopped beverage alternative with fewer calories and less sugar, so you get the flavor edge, but without the ABV. Many have jumped on the distillery train by adding RTDs or FMBs to their lineups, like Dry Dock and SanTan. And now, others are looking to pivot into hemp-derived THC beverages to add revenue to their income statements thanks to a loophole in the 2018 Farm Bill. Craft brands like 8th Wonder, Hopewell, Field Day, Bent Paddle, Indeed, and Urban South are betting big on the hemp-derived THC beverage game. Still, others are going even further by entering the more serious dispensary scene with marijuana-derived THC beverages that hover above the 0.3% threshold of regulation – like Union Craft Brewing, Two Roots, and Ceria. Let’s also not forget that beer has always been closely associated with food, so it only makes sense that food products are another revenue stream to add to the mix. However, it is less popular and not a windfall unless your brand is big enough to rest outside the BA craft brewery definition.

Despite the current challenges, craft breweries have hope on the horizon, even if it’s far in the distance. The industry has shown resilience through innovation and adaptability, proving that tough times can lead to strategic growth and diversification. Craft breweries are finding new ways to navigate the economic downturn. Moreover, industry analysts and historical data predict a market rebound in 2026 and beyond, promising better times ahead, but brands must weather the storm first. As consumer preferences continue to evolve, the craft beer industry is well-positioned to thrive again, with opportunities for growth and renewed consumer interest. So, as breweries adapt and restructure, they can look forward to a future where craft beer returns to its former glory on tap walls and shelves nationwide, and we can all raise a pint together for adversity.

[ad_2]

Source link